9†††† Dollís Houses

here

is no

record as to who built the earliest dollís house, but there is an inventory of

one that was made in Nuremberg for Albrecht V of Bavaria in 1558. It was

originally intended for his daughter but when it arrived he decided that it was

far too nice a toy for her and put the house in his own art collection. The

dollís house would almost certainly have contained toys made of silver.

It was

roughly 50 years later that dollís houses of German design started taking

shape. Christopher Weigel is known to have written in 1698.

The

desire of adults to buy dollís houses started in Germany, spread to Holland and

fifty years later became established as an English hobby, primarily for adults,

or so it is assumed.

In

England, during the eighteenth century, the doll was already established as a

childís baby, so that when dollís houses appeared in England they were called

baby houses. There are many superb examples of doll, or baby, houses in the

museums of the United Kingdom. There is a fine collection of baby houses or

dollís houses at Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood, London. In fact the

Westbrook baby house which was once in the Victoria & Albert Museum has now

been moved to the Bethnal Green Museum.

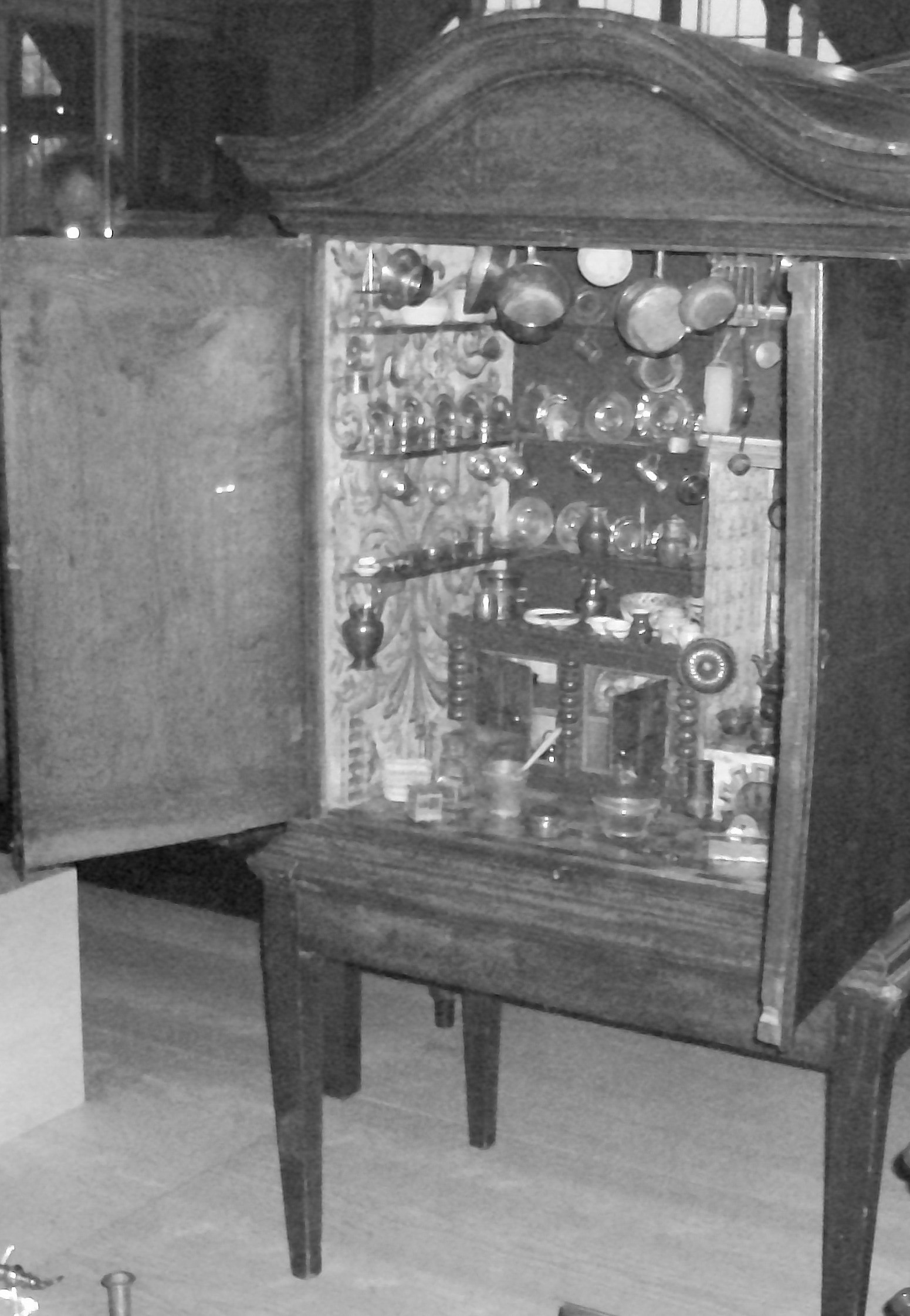

The

wealthy Englishmen returning home from the continent brought with them the

Dutch ideas of having portioned cabinets standing on legs, out of range of

sticky-fingered children, where the adults could view and keep their treasured

possessions. These cabinets were similar to the Dutch dollís house, except

their dollís houses had two doors on them that when shut made them appear to be

ordinary wooden cabinets. When the doors were opened all was revealed, a

dazzling display of decorated and furnished rooms in the Dutch style. Those

owned by the wealthy folk were furnished with gold and silver household

fittings, while the lesser well off had to be content with brass and pewter.

In

England, the tall secure cupboard for hiding adultsí treasures eventually had

to give way to Ďsquattersí, as childrenís tiny dolls moved in. It was only a

matter of time before the English dollís house as we now know it came into

being with its elaborate front of house decoration and opening out to display

equally tastefully decorated interiors. These early dollís house were usually

locked, as many contained expensive silver furniture fittings, kitchen

implements and utensils. Around 1700 the English decided it would be nice to

have their baby houses with a full frontal view like an ordinary house with

doors and windows, and so the modification began to what we recognise today as

a dollís house.

In the

Geffrye Museum in London, there is a surviving dollís house of the early proto

type Dutch design, owned once by John Evelyn (see below, Figure 5, p. 62).

These houses were exact replicas of actual houses of that period.

There was

no limit to the extremes the owners would go to make their particular dollís

house as authentic as possible. The dollís house of Petronella Oortman, built

c. 1690 and now housed in the Rijksmuseum, even has silver displayed in her

dollís house cupboards, exactly as a bride would have her dowry. The money

spent on furnishing these houses more than suggests that these dollís houses

were used extensively for amusement by adults.

††††††††††††† Figure 4†††† An

early Dutch dollís house, c. 1800. Courtesy of Bethnal Green Museum.